69th TDC Annual Competition Winner

„Democracy is just like a child. We don’t just give birth and let it grow; we have to take care of that child to prevent it from going in the wrong direction.”

Interview with Saber Javanmard

by Sofiia Lutskiv & Varvara Slastsenkina

(June 2024)

First of all, we would like to say that your project, Women, Life, and Freedom, truly captivated us. I am from Ukraine and Varvara is from Belarus, so we really understand how important it is to raise awareness about protests in any possible way. As designers, we feel it’s especially important to integrate our skills into this effort. Can you share a personal story that left a significant impact on you and prompted you to create this project?

Well, I live in the Netherlands, and I usually go to Iran once a year. I had planned to go there in August 2022. But then, in September, the death of Mahsa Amini happened. A week later, I realized this was not just a simple event. It wasn’t just a movement; it was a revolution. I sensed it. I had a similar experience in 2010 with the Green Movement. Back then, I was living in Iran, and it escalated quickly before dying down within three or four months. But this felt different. Living here, like many other Iranians abroad, the first question was: what can I do? How can I help my people? This leads to a kind of depression because you can’t help much. You can’t join the demonstrations, for instance. So the project started like this. I was glued to the news, doing nothing else, especially in the first weeks. One slogan caught my attention, and I wrote it down. I shared it on social media to see the reaction. The next day, I did it again. It became a ritual for me to calm down and feel like I was doing something. But it became serious quite fast, within two weeks. Back then, I didn’t have a studio and was working at the kitchen table. The artworks were lying around, and my partner suggested documenting them. We often discussed how things were in Iran, the state of journalism, and the media’s reaction.

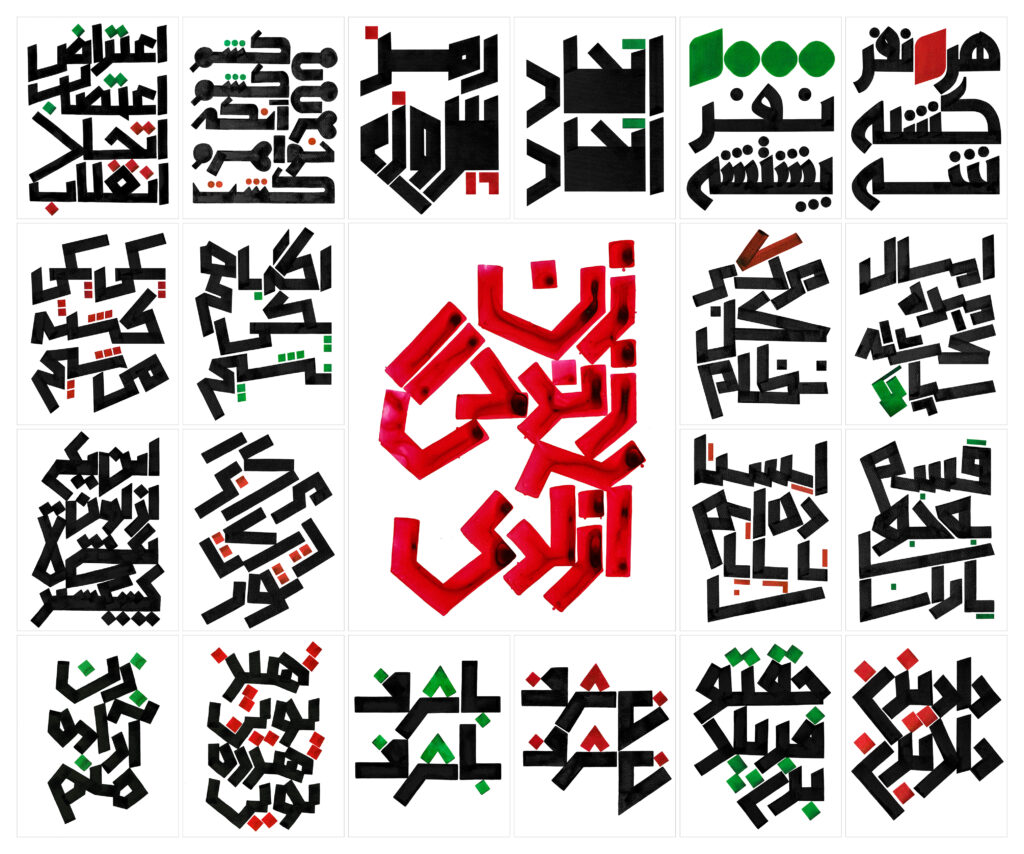

I explained that everything was blocked, and there was no way to document events because anything related to the movement or revolution would be boycotted by the regime. I realized that documenting these slogans had never been done in our history (in a typographic way). Iranian or Eastern culture is very verbal, and we don’t have many documents from the past. This applies not only to politics but also to many other things such as music. There aren’t many notes about musicians from 500 years ago, for example.

So I thought, let’s document the slogans for future generations. During the Green Movement, I was in the streets, hit by the police and guards, but after ten years, I realized I didn’t remember many of the slogans we shouted, except for the main ones. That was why I started documenting. But it was a difficult process in the beginning. There was no strategy, nothing. It was just an expression.

Yeah, I truly understand you because we have the same situation in Belarus.

I’m sorry really about that. One more thing to add: the first slogans I wrote or made into graphic elements and typographic posters were created with a lot of guilt. I thought, well, I’m sitting behind my little table, having my coffee, and writing things while people are getting killed there. But later on, I realized someone needs to do this. You cannot be in the demonstration and document it at the same time. We need a musician to make a song. We need a typographer to document. That realization gave me a calming feeling, knowing that what I’m doing is important and not useless.

You definitely made a big impact. We truly liked your work and because of that we explored information about the revolution and Iran itself. This is a way to learn about problems, by something you are interested in, in our case, design. In our academy, professors teach us to implement art into different spheres of our life, to take part in it that way. And we do as much as we can right now. And I want to ask whether you get any threats from Iranian government because of your work?

Well, simply, I cannot go to Iran anymore. I got news from a family member who has a friend in the intelligence office. He told my family to inform me not to come to Iran; otherwise, I would be arrested. On social media, I was threatened like any other designer or artist, with messages saying, „We will find you, we will take you down,” etc. But, I’m very used to that. I know an Iranian cartoonist who lives in Amsterdam. One day, she opened her door, thinking it was the mailman, and was hit by two guys. I realized this could also happen to me. But on the other hand, we knew this challenge from the beginning.

I wondered if I should play it safe, using only some hashtags and mixing them with my projects—doing something but not committing. Sharing something occasionally and that’s it. But then I thought, well, that’s not going to help anything. It’s better to accept the consequences. Knowing the consequences, I decided to either fully commit and accept them or back off and do nothing. It can’t be a grey area, somewhere in the middle. That’s not how it works. So that was the decision I made. Then the fear was gone because I accepted it. I was ready for it. I put myself on the front line of the battlefield. Well, maybe not the first line, but at least the second line. So it’s fine. It’s okay.

We are really sorry to hear that you cannot go back to your country and really hope that one day you will.

I will be there, and we will celebrate. That’s not a problem. But I told this story because I want to say that freedom is not a gift from God or a raindrop that comes down suddenly. We have to fight for freedom. We have to earn it. This applies to any free, democratic country. For example, the Netherlands is a democratic country, but if we don’t pay attention to freedom and democracy, it will disappear quickly.

Democracy is just like a child. We don’t just give birth and let it grow; we have to take care of that child to prevent it from going in the wrong direction. We see this in some countries, like Italy, which is going in the wrong direction. Or with the upcoming elections in the States, things can easily go that way. Fighting for and taking care of democracy and freedom is a daily practice.

Have you received any feedback from people which are directly affected by the process? Or maybe take part of it?

Well, the best feedback I’ve ever received was from a lady, I guess from the north of Iran. She saw an Instagram post or story of mine shared by others. She took a screenshot, printed it out, framed it, and mounted it on her wall. A friend of mine sent me a picture of it. Then I got in contact with her and asked why she printed it out. She said she was looking for something she could see every day on the wall to motivate herself to go out and fight for the revolution. She said it caught her eye because it was really to the point – no decoration, no fancy graphics. Later, I sent her the high-quality print-ready file so she could print it out. Another example was a lady living in a neighbourhood in Tehran, just 500 meters from Evin prison. She saw the „Woman Life Freedom” t-shirts I made to raise funds for charity. She asked me to send her the file so she could print and wear it in the demonstrations. But I never sent it because I thought it was too dangerous.

But that kind of feedback was one-sided. On the other side I received a lot of threatening or critical messages on Instagram, like: „Oh, you’re sitting there having your fun party, drinking beer, and making some crap.” That was exactly the word they used. In response, I shared a video of myself drinking shot after shot, crying, and writing to show that I wasn’t okay. No one is okay. No one is happy about this situation. I explained that I was doing this for them. I have a calm life here; everything is going well for me. So I have no personal reason to do this, except that I still think of myself as Iranian, and I should do something for my own family and my bigger family. But I don’t know if it was convincing or not.

I think the problem is that people argue who feels worse because of the overflowing emotions, but it is terrible for everyone who is involved. How do you balance your emotions with the responsibility of accurately representing such a significant political event?

How do I balance it? Well, if I go back to the beginning of the revolution, there was no balance. As I explained, I was drinking, mourning, and creating. But at some point, I had to think of this as my full-time job. So, no emotions—focus on the work and turn it into a kind of product (an awful word for such a tragic event). What am I going to share? How am I going to share it? How will I interact with the audience?

Living abroad meant I could bridge what was happening in Iran with the Western world by raising awareness among Western people. Western people had limited access to accurate media, relying mainly on national media or YouTube, while we could receive the news directly from the people inside the country. So, one of my goals was to translate the slogans and put them in a Western context that people here could understand. This could open up a discussion about why Western people need to support the revolution. In my typographic practice, I developed a strategy for documenting and sharing the slogans while implementing typographic elements. It took a couple of months to achieve that strategy, but there was no balance. There is still no balance.

What was your process of transferring real slogans and placards into your work? And about typography of it? Especially the meaning of Arabic symbols.

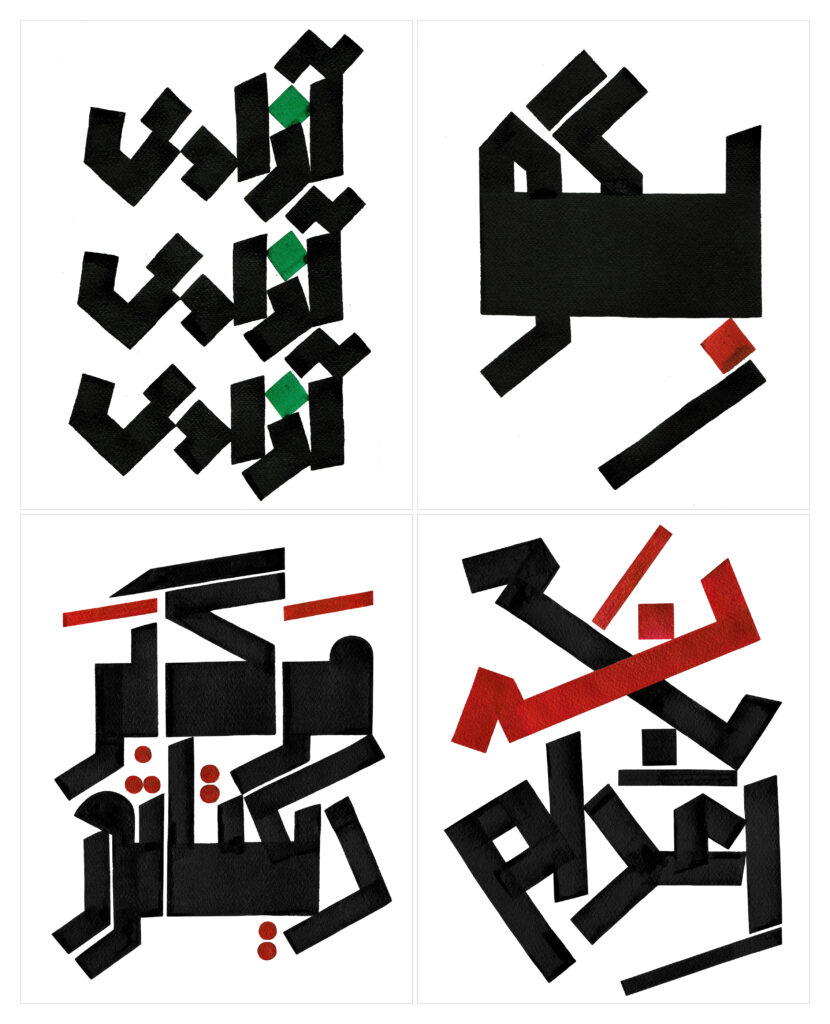

First of all, there was no chronological order for the slogans; some slogans were created by people much earlier than when I made them into posters. But I didn’t have the time or another reason to include them. Plus, my choice was based on which slogan was important or highlighted at that moment. It was a back-and-forth process. We had some less revolutionary days that allowed me to list the slogans and make clear choices. I also wanted to apply inclusivity to the documentation by choosing slogans made by Azeri or Kurdish people. Regarding the typographic elements in Arabic and Farsi design, I read a sentence by a friend who said: „Please don’t spoil the revolution with fancy, decorative graphics.” It meant: First, don’t turn the revolution into a business. Second, don’t add decorative elements to the posters. This stuck with me.

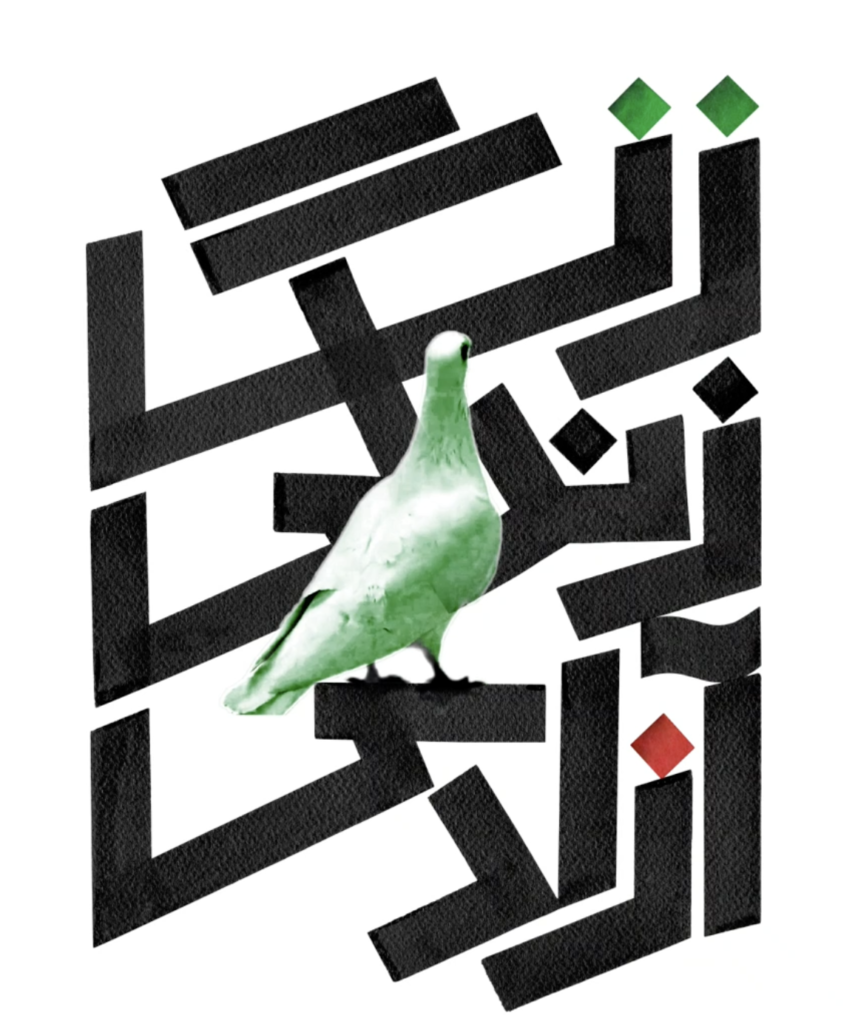

The slogans were clear, and so was my task as a designer: no multi-layered graphics and no confusing design – only clear visualization to convey the message. My first sketches, which I never shared, were based on nostalgic scripts like 'Thuluth’ or 'Nastaliq’ script. But after my visual research on the placards, I realized the significance of time for ordinary people; they used whatever they have around—a piece of cardboard, a wooden plate, and any possible writing material. They wanted to be in the demonstration. This helped me approach a quite direct visual language, with sharp edges and low-contrast brush strokes. Iranian scripts often have high contrast, making them more elegant. But I went for monoline letters. The reference I had was one of the scripts called 'Kufi.’ Kufi script is the oldest script in Islamic calligraphy. But I used it in my own way. I also made the tools for that. You asked about the typographic elements, and that was something I was doing at the moment. The decisions I made were quite fast and sometimes wrong; there was no time for deliberation. If I were to review my posters now, maybe I would change them, but I didn’t have time for that since we were living in that moment. The process was totally different from a regular graphic design assignment.

Yeah. So, one more pressing question. In connection with recent events, how do you think the death of the president of Iran, Ebrahim Raisi, is affecting society, and are you planning to create any project related to this?

Well, I made a 10-second video for that, and that’s it. But as for the first part of the question, no, it’s not going to leave any impact on society. He was someone we would call a fly. Imagine an annoying fly in mid-August. It’s warm, and you just want to sleep. What do you do? Smack it, and it’s done! He was just a puppet for the Iranian supreme leader, and the larger political power, IRGC. Essentially, he started as a nobody. Raeisi was the most obedient person to the supreme leader. His life or death didn’t truly matter to the regime or society. He was there and disappeared just like a fly. I must say, like many other Iranians, I was happy when I heard the news. I was glad that one of the dictators was gone. However, on the other hand, I felt sad and angry because his death was not fair. It happened in a few seconds. He should have been taken to a fair court and spent the rest of his life in jail. Still, it’s better than nothing. There will be new elections in Iran, but I am not following them, and I won’t be voting for any of the candidates. I think it’s useless to vote when we don’t have democratic elections.

Yeah. Thank you. Is there any message you’d like to leave or anything else you’d like to add?

I’m still paying for the project I’ve done. Let’s not call it a project. it was the smallest contribution I could make to my country and my people. I did this for the next generations to remind them what happened in our contemporary history. We need documentation. Otherwise, we will just easily forget the things. I’m still dealing with the consequences, talking to a psychologist. There were even moments when I considered ending my life. But then I thought, this is exactly what the regime would want. My existence is a threat to the regime. But the only thing that will happen after my death is that those who love me will miss me. I thought of my partner, my family, and my best friend, Harry, my dog.

As I mentioned, democracy, freedom, and all our values are not gifts; we have to fight for them and accept the consequences. Nothing will happen to the world with or without me. But if my life can contribute to taking a step toward freedom, I’m fine with that.

I personally want to say thank you so much for these words.

Oh, we only have to fight. I mean, look at it. It’s an awful planet. It’s getting worse and worse. I remember just a couple of years ago we were focused on the environment, climate change, and so on. But now, we don’t even have time for that. It’s not even in the news anymore because of Palestine, Israel, Ukraine, Russia, and more conflicts popping up. So congratulations to our wonderful world.

We wish you luck. And thank you so much for sharing your story with us.

You’re very welcome. Is there anything else you’d like to share with me?

As Ukrainian and Belarusian, we both have faced these awful things in the world in a quite young age. I’m 17 and it was really important to hear your words, your support and what you said because sometimes it feels like no one understands you and you’re doing nothing and you could do so much better.

Oh, no worries. In the end, we are all together in this, sharing the same values. So, we must fight for our values. At the moment, I’m not actively involved in 'Women, Life, Freedom’, but it’s close to my heart. I need to focus on my recovery, and then I will return stronger.

Last but not least, you have the best weapon as a designer. A pen is much stronger than any gun. As a designer or artist, you have that pen and many more tools, so please use them.

The material has been created as part of the Spring 2024 Semester assignment for the Elements of Visual Communication Theory (EVCT) course, conducted by Dr. Monika Marek-Łucka at the Polish-Japanese Academy of IT in Warsaw. We would like to express our gratitude to the designers awarded at the TDC Annual Competition for contributing to the creation of high-quality educational materials.

Illustrations source: https://www.oneclub.org/awards/tdcawards/-award/46195/woman-lifereedom-documentation-of-slogans

Saber Javanmard Studio: https://studiosaber.bigcartel.com/products